At a recent “Science of Consciousness” conference, I attended a session on “Descriptive Experience Sampling.” Two researchers demonstrated their technique of interrupting consciousness. A volunteer wears a pager that sounds at random times during the day. When it goes off, you are supposed to write down what you were thinking at that exact moment.

At a recent “Science of Consciousness” conference, I attended a session on “Descriptive Experience Sampling.” Two researchers demonstrated their technique of interrupting consciousness. A volunteer wears a pager that sounds at random times during the day. When it goes off, you are supposed to write down what you were thinking at that exact moment.

The researchers demonstrated by having a tone sound at random times during their presentation. When it went off, often in the middle of a sentence, everything stopped and we all wrote what we had been thinking in the “last undisturbed moment” of consciousness before the tone.

Usually people reported the last thing they had heard, what the speaker had been saying when the beeper sounded. One person said that when the tone occurred, he had been fuming in annoyance at a groundkeeper’s whining lawn mower just outside the window.

My thoughts seemed to run in different channels. I tracked the words the speaker was saying, but my attention was focused on his deferential attitude to the other researcher, Russ, the older man, who invented this method years ago. Russ was seated, staring into a computer screen, while the speaker, Eric, was saying, “Now my own research is more theoretically oriented than Russ’s…” That’s when the tone sounded, so I wrote that phrase down, just as he’d said it, but that wasn’t my full thought.

I had been watching Eric’s gesture as he said that phrase. He had turned from the audience towards Russ and extended his hands, palms up, toward him as if to offer him to us. Here he is, The Great Russ! He was presenting Russ to us on a silver platter. Russ paid him no obvious attention but probably noticed the large gesture in his peripheral vision.

What odd behavior, I thought. It told me that Russ was the senior partner, the man in charge. Eric was only there at the conference because Russ had invited him along. Russ owned this project and Eric’s reflected glory depended entirely on Russ. So strong was this invisible tether to Russ that Eric wouldn’t even think of comparing his own research (and that’s how he said it – emphasis on the word, ‘own’) to the unassailable work of The Great Russ, unless he was very clear with his subtext: ‘But hey, we know this is not about my research. This is all about The Great Russ.’

What odd behavior, I thought. It told me that Russ was the senior partner, the man in charge. Eric was only there at the conference because Russ had invited him along. Russ owned this project and Eric’s reflected glory depended entirely on Russ. So strong was this invisible tether to Russ that Eric wouldn’t even think of comparing his own research (and that’s how he said it – emphasis on the word, ‘own’) to the unassailable work of The Great Russ, unless he was very clear with his subtext: ‘But hey, we know this is not about my research. This is all about The Great Russ.’

And that’s when the beeper sounded. My observation of the social relationship between the two men took me a lot longer to describe than the thought it sprang from, which was as fast as the event was unfolding in real time. Writing it out was like trying to write down a dream. You can write for a half hour trying to catch a single fleeting dream element.

The actual words Eric had been saying were a tiny fraction of what had been going on at that moment, and not even the most interesting part. Yet the subsequent group discussion focused on whether or not the audience had been ‘paying attention’ to Eric when the beeper went off. ‘Wasn’t your mind drifting into other areas?’ the challenge went.

Well no. I was not drifting at all. I was paying very close attention, just not to what Eric thought I should be paying attention to.

So with this little observation, I ended up with two thoughts that could fuel psi-fi stories.

- What you think is going on is not necessarily what I think is going on, even when we are ostensibly ‘sharing’ the same experience, even when you are talking and I am listening. What you think you are saying is not necessarily what I am hearing, though I am listening very carefully.

So imagine a character in a story, a highly intuitive psychotherapist perhaps, or an ordinary person with some technological gizmo that allows her to take a sample of other people’s thoughts, like a scientist taking a bore out of a tree so the rings can be counted. The character would know what the other person was really thinking, even if, as in my example, the speaker was probably not fully aware what he was thinking. One interesting consequence is that the character, call her Gizmo Girl, could not be lied to. She would know what you were thinking even better than you did yourself. That would be especially interesting if she were a detective, or an industrial spy, or entangled in a romantic relationship. What would she do with the information?

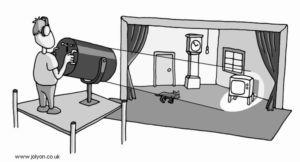

- What do you ‘pay’ when you ‘pay attention?’ The crux of the research method of this session was that the beeper interrupts your thoughts. In other words, it redirects your attention from ‘out there’ to ‘in here.’ How does that work? The Great Russ kept using the phrase, ‘in the footlights of consciousness,’ as if there were a lot of things going on in your mind but only one or two things were in ‘the footlights’ at the moment the beeper went off. It was a Cartesian ‘Theater of the Mind’ metaphor, derived from philosopher Rene Descartes, who, in the 1600’s suggested that the mind was like a theater and we ‘paid attention’ by observing whatever was on stage at the moment.

That idea is discredited because it requires a ‘little man in the head,’ a guy in the audience of the mind who looks at the stage and ‘pays attention’ to what’s there, what’s ‘in the footlights,’ as The Great Russ liked to say. But there is no little man in the head. If there were, he would also need to have a mind, and inside his mind would be another tiny theater of the mind, with an observer of it, and that would require an even tinier, littler-man-in-the-head, … and it would be turtles all the way down. No good.

That idea is discredited because it requires a ‘little man in the head,’ a guy in the audience of the mind who looks at the stage and ‘pays attention’ to what’s there, what’s ‘in the footlights,’ as The Great Russ liked to say. But there is no little man in the head. If there were, he would also need to have a mind, and inside his mind would be another tiny theater of the mind, with an observer of it, and that would require an even tinier, littler-man-in-the-head, … and it would be turtles all the way down. No good.

If we rule out the homunculus (the technical name for the mythical little man in the head), and all supporting metaphors of stages and spotlights and footlights, how should we understand attention? What is it, and how do you ‘pay’ it? What really happened when the beeper went off and my ‘attention’ was redirected from Eric’s words to my thoughts?

I wonder if it was. I was always in a mental space that was a blend of what Eric was doing and what I thought about it. It wasn’t one or the other and the beeper didn’t switch me from out to in. That binary is primitive.

What about a psi-fi character who has the opposite of Attention Deficit Disorder? He has hyper-attention and misses nothing, ever. Not one molecule of experience gets past him. You and I kind of tell ourselves a story in general terms about what is going on, focusing on a few details, but Hyper-Att-Man actually attends to every detail, all the time. His attention is like multiple klieg lights that illuminate every hair on your head, every bump on your nose.

He certainly would make a fine witness to a crime, but maybe not a very good sports reporter, because he would have so much information, he wouldn’t know what to report. If everything is important, nothing is important. The batter would hit a home run and he would report on the texture of his shoelaces.

And if his attention was a hundred percent on the ‘out there,’ and zero on himself, he would be no good at analysis. He’d be too busy observing to think about anything. Could he understand anything at all? I often wonder about that in people who seem very externalized.

Maybe Hyper-Att-Man could ‘focus’ his extraordinary attention like a lens zooming in. In a crowd, he would see every detail of every face, hear every breath of every voice, and yet could focus on one detail, like those fantasy computers in spy movies where the crabby case leader barks ‘Enhance!’ and the scene zooms in on a face. What could the character do with that ability?

Maybe Hyper-Att-Man could ‘focus’ his extraordinary attention like a lens zooming in. In a crowd, he would see every detail of every face, hear every breath of every voice, and yet could focus on one detail, like those fantasy computers in spy movies where the crabby case leader barks ‘Enhance!’ and the scene zooms in on a face. What could the character do with that ability?

He might be a great detective or a great criminal. A great scientist? A great athlete? In an alien encounter, he would be the guy on the team that noticed the one tiny detail about the aliens’ behavior that clued the Earthlings into the key they needed to defeat them.

It’s not a finished idea, but it’s a psi-fi input.