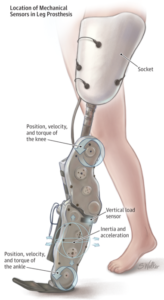

Illustration by Samantha Welker. From http://news.feinberg.northwestern.edu/2015/06/building-a-better-prosthetic-leg-for-amputees/

A couple of recent articles in The Economist newspaper caught my attention because of their implications for the distinction between sci-fi and psi-fi. One article announced that Elon Musk, founder of Tesla and SpaceX, has started yet another company, Neuralink, “… to make invasive devices for treating or diagnosing neurological ailments.” (“We can remember it for you wholesale,” The Economist, April 1, 2017, pp.71-72).

The idea is to implant electrodes into a human brain in order to read and write information directly between brain and computer. The idea has already been partially implemented in laboratories where paralyzed patients use their thoughts or imagination to control prosthetic limbs (“Moving moments,” The Economist, April 1, 2017, pp. 72-73).

At Case Western Reserve University, a paralyzed patient was fitted with electrodes in his left motor cortex that sensed activation of about a hundred neurons when he imagined moving his right arm. The electrodes pick up that neural signal, send it to a computer which controls the robotic prosthesis, and that allows the patient to pick up a fork and eat.

Now if I were writing sci-fi, I would take that technology and imagine it into a future where even ordinary people use brain implants to enhance their strength, coordination, or athletic performance. With computer augmentation they might have super-senses, able instantly apprehend full detail, from the barely visible to the cosmic, in a flash. They could pinpoint the source of a sound, no matter how vague or far away, to the nearest millimeter. They could discern the composition of food by smell, detect drugs and explosives better than a dog. They would have never-fail memory bigger and better than an Oracle database. Like moving a prosthesis, a hero could learn to move any number of objects in the world by thought, using micro-bots, creating a scientifically plausible form of psychokinesis. Lots of good sci-fi story potential there.

For comparison, what would the psi-fi stories be? They would start with the phenomenology, or experience of cognition, not with the technology. For example, is it really true that memory is a matter of storage and retrieval, as in a computer? Most people believe that, but research on human memory strongly suggests otherwise. For autobiographical memory especially, memory looks more like a creative construction, more like a dream than a recording, which is why eyewitness testimony is so unreliable.

So a psi-fi story would develop the idea of memory as a delusional construction, delusional because the character believes it as fact, but from an omniscient narrator’s point of view, the truth could be wildly otherwise. Psychological, motivational reasons would explain the form a person’s memory reconstruction takes. A lot of good novels have already been written on that theme: reality turns out not to be as remembered.

Another psi-fi story with a bionic theme would have a character who suffers a great injury then is rebuilt with the best in computer-controlled prostheses, everything from titanium hips to tens of thousands of brain electrodes. She gradually becomes a truly bionic person, nearly all of her thoughts routed out to the computer for expression in computer media (like Stephen Hawking), or routed back to the body for movement.

Image courtesy technopolis.blogspot.com

Agency, or free-will, as it used to be called, is gradually transferred from the character to the computer, so slowly that she doesn’t notice the day to day changes. But at some point it is the computer, not her, reacting to sensory experience and executing her brain impulses. The psi-fi question is about how much agency a person can give up and still be a person. Does she lose her sense of self? Would she keep her personality? If she had been religious, would she still have faith?

In these quick examples, the psi-fi stories are about the person, not the computers. The questions are psychological, not mainly technical. The information technology is used as a device to highlight and isolate a particular aspect of human psychology, and that’s where the real story is, and that’s where psi-fi takes us.

Hence the psi-fi slogan, “It’s not about the robots.”