In this 1968 classic the world has been destroyed by whatever, humans evacuated to Mars, with only a few left in the rubble of what had been civilization. Nevertheless we must assume a large and robust manufacturing industry somewhere that provides all the flying cars, laser guns, food, fresh water, sanitation, electricity, broadcast television, and communications systems. Though plants and animals have gone extinct, characters eat tofu (soybeans) and cheese. But these are quibbles.

In this 1968 classic the world has been destroyed by whatever, humans evacuated to Mars, with only a few left in the rubble of what had been civilization. Nevertheless we must assume a large and robust manufacturing industry somewhere that provides all the flying cars, laser guns, food, fresh water, sanitation, electricity, broadcast television, and communications systems. Though plants and animals have gone extinct, characters eat tofu (soybeans) and cheese. But these are quibbles.

Human-like androids serve as workers on Mars and every once in a while some of them escape to Earth where they must be hunted and “killed” by bounty hunters like Rick Deckard. In this novel he hunts and kills six andys in two batches of three. That’s the very simple and kinetic hunter and hunted story that animates the action of the novel.

The main interest comes not from Deckard’s activities, but what he thinks about his work, about androids, and about life. He knows the andys so well that he is borderline empathic with them, and that is a problem because they are not empathic and will kill you as readily as look at you. Nevertheless, he manages to bed a female andy, which is illegal and immoral, though not unfaithful to his wife, because machines “don’t count.”

Another problem is discerning who is an andy and who is a human. The androids have become so good that even the most sophisticated test (a kind of polygraph) is not perfect. That raises the question: why then is it okay to kill them? The motivation for the original Turing Test is turned upside-down. Instead of finding out which machines can pass for human, the new test must reveal which apparent humans are really machines.

The andys have a preprogrammed four-year lifespan but that fact doesn’t really figure into the novel. It is also not clear why andys would want to escape from Mars to Earth, except, it is lightly suggested, to escape their role as servants, but as machines, they shouldn’t care about that, so the andys are not well-motivated. Perhaps one should expect that of a machine.

The electric sheep of the title is a red herring and a running gag. A robotics company (with unexplained materials, engineering, and marketing resources) manufactures electric animals for people who want pets. A few live, DNA-bearing animals are known to exist but are extremely expensive. Deckard has an electric sheep but longs for a real, live animal. An android, presumably, would never have that longing, although no android is explicitly asked about that in the novel.

The tone of the novel is thoroughly dystopian. Everybody is depressed and uses an electronic device (instead of pills) to manage moods. The scenery is dark, with acres of abandoned apartment buildings. Rooms and streets are filled with rubble.

As in other Dick novels, a tone of social satire also runs through the story, in this case a parody of a crazy state religion and of electric animals salesmen that sound like used car dealers. And like other Dick novels, there are plenty of hallucinogenic scenes where the world simply starts to melt or dissolve for no particular reason. Keeps you on your toes.

Overall, the book is a monument of sci-fi creativity and the novel that really defined the main problem of AI – what is the test that distinguishes a very advanced android from a human, or to put it another way, what makes a human distinctly human, if anything?

The original (1982) Blade Runner movie captured the dystopian atmosphere of the novel perfectly with its film-noir chiaroscuro lighting and steamy, smokey, green squalor. The movie kept the basic plot line, Decker is a bounty hunter (Blade Runner) who must hunt and kill six illegal androids, which he does. Decker’s emotional ambivalence about the andys does not come through as strongly in the movie, which is more of an action piece than a contemplation of what it means to be human. He almost, but not quite has an andy girlfriend, and that’s the full extent of his moral quandary. The social satire is dropped completely, as is the concept of electric sheep and other animals.

The movie thus is only very loosely related to the novel. It is basically an action picture similar to The Terminator, with extremely good art direction and music. It’s a work of art but not a tale of ideas.

The new Blade Runner 2049 (2017) has neither the ideas of the novel, nor the cinematic beauty of the first movie. The andys in this version are well-motivated: they are unhappy with their four-year lifespan and want more. Decker shoots them anyway, and that’s about it. The three-hour (!) picture burns up the screen with cheesy special effects rather than story or character development or cinematic art. The substitute story is a variation of the limp and time-worn melodrama, “Who was his real father?” My thought was, “Who cares?”

Being more generous, the “writers” were trying to pose the question, would there be any justification for discriminating humans and androids if andys also could reproduce – with a human mate? In other words, what would it take for humans to morally accept androids into the fold of humanity? Unfortunately, that theme was all but lost in a sea of irrelevancies, visual non-sequiturs, and ear-damaging sound trying to substitute for emotion. Anyway, the obvious answer is “empathy” not “reproduction,” so the main theme of the story ends up seeming just dumb. PKD would spin in his grave.

The novel stands as a pinnacle of psi-fi literature, getting directly to the central question of what is the “essence” of human consciousness. The first movie largely avoids that question but succeeds as a lovely exercise in film-making. The second movie tried to get back to the original psi-fi question but failed, probably due to too much Hollywood money without creative push-back.

The definitive psi-fi android movie has yet to be made.

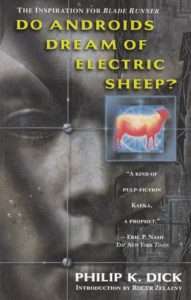

Dick, Philip K. (1968/1996), Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? New York: Del Ray, 244 pp.